Practice When It’s Windy

By Thomas R. Dempsey, M.D. CCI

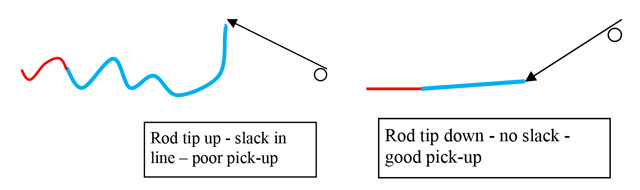

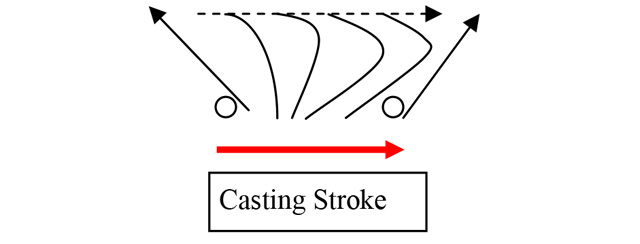

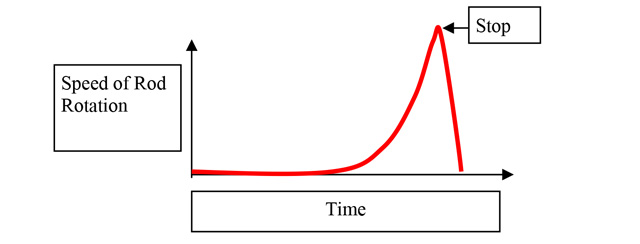

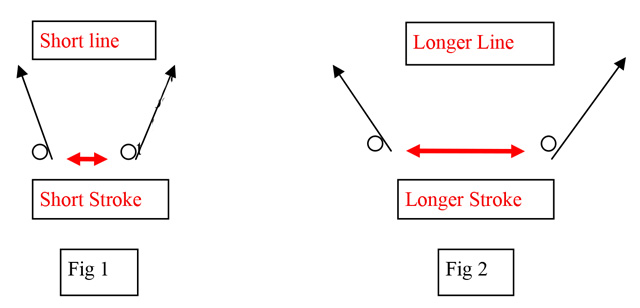

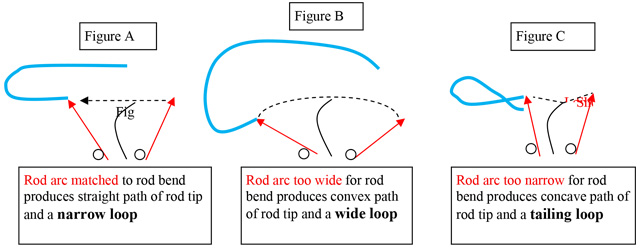

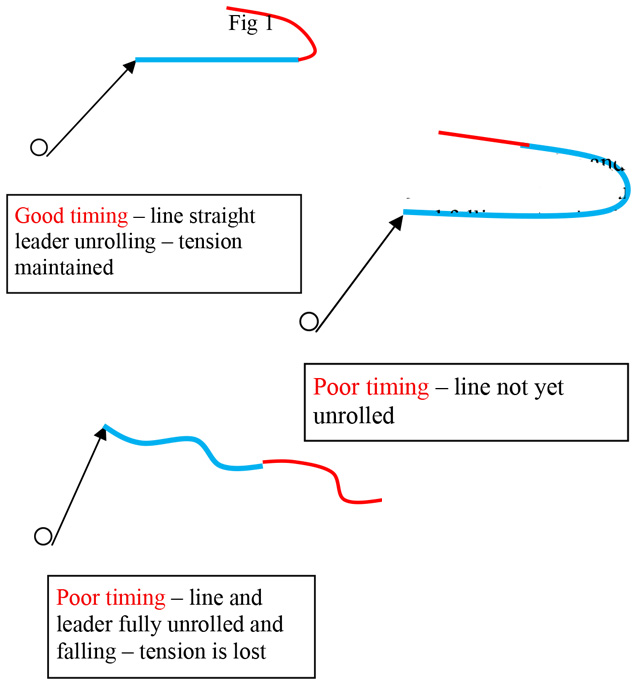

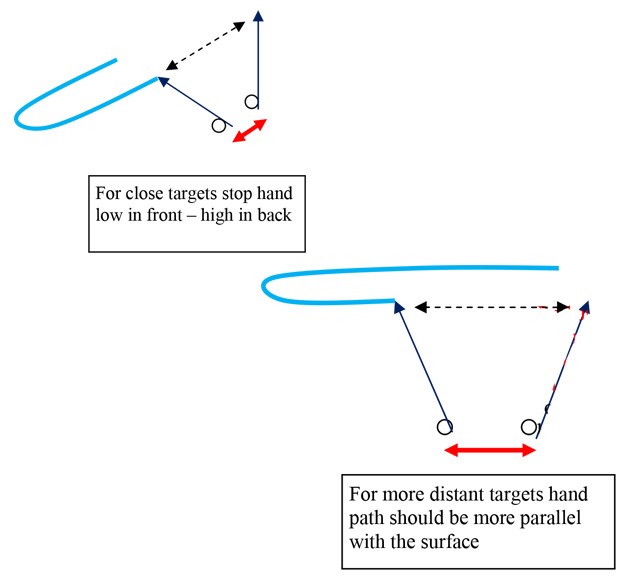

They say when it’s windy, you can sit at home and complain, fish and fight the wind, or use the and to your advantage. With a little practice, you can handle almost any degree of windy conditions. First, let’s take a wind blowing straight into your face. The problem is simply resistance, the wind is the roadblock. To penetrate it, three issues must be addressed. 1.tight loops-A tight loop is like a sharp arrow, it penetrates. In order to cast a tight loop, you have to cast keeping †he rod †ip moving along a straight line course, otherwise you will throw a large open loop that is less effective in penetrating the wind. 2.speed- Remember your high school physics, KE [kinetic energy] = 1/2 M [mass, or the weight of your fly line] V [velocity]2[squared]. This means the faster you cast the more energy or force you generate. You can’t change the mass or weight of your fly line but you can change the velocity or speed at which you cast, resulting in more force, simple, right? 3. Trajectory- This is the pathway your line travels during the cast. If you cast up a bit on the backcast and down a bit on the forward cast you expose your line on the forward cast to the wind for a shorter period of time it before it gets to the target. You are tilting you casting plane slightly down. There are two other ways to help when casting in the wind, use a faster like a tip flex rod and a heavier line, no brainer.

How about wind from a behind? Same problem as with wind in your face except in reverse. Again, tight loops in to the backcast with speed. Some casters cast a bit DOWN on the back cast and UP on the forward cast to try and take advantage of the “kiting effect “ of the wind from behind. Reframe from shooting lots of line into the backcast. You’re just making it harder by throwing slack into the cast. This is a time you might want to haul harder on the forward cast again taking advantage of the push of the wind from behind.

Wind into the line hand, your left side if you cast right handed. The problem here is that the wind blows your cast off target. You have to compensate by casting to the LEFT of your target if the wind is from the LEFT and you are right handed. Now it’s a whole different ballgame if the wind is blowing into your rod hand, the hand you are casting with. Not only are we dealing with an accuracy situation, there is the element of keeping the fly from being blown into the caster, SAFETY. For low winds cast more horizontal, or you can try a Belgium cast. For a stronger wind, cast over the opposite shoulder by bringing the rod to the same position you would use if there was no wind and angle the tip over the opposite shoulder. This allows you to cast with the same mechanics as you would with no wind but with the pathway of your cast now over the opposite shoulder. With severe wind switch to a backhand cast or better a Barneget Bay cast. That is a cast facing away from the wind, casting in a horizontal plane, with a forehand grip on the back cast as well as the forward cast. Or you just may learn to cast with the opposite hand, how about that? So now you have the formulas to handle the wind from any direction, tweeking each formula if the wind happens to be at an angle. Always remember the five essentials still must be adhered to in order that you get the most from your four formulas for casting in the wind.

Practice when it’s windy.